A few days before Thanksgiving, United Furniture sent an untimely message to its staffers.

The company laid off “nearly its entire workforce,” The Daily Beast wailed, “via text and email … while many of them were sleeping,” and “in a heartless parting blow, discontinued the employees’ health-care benefits.”

Yes, 2,700 households in three states will have a rather blue Christmas in 2022. Times are tough in The Land of the Free, and they might get a lot tougher.

But what are the odds that The Daily Beast will cover the “punch to the gut” the tens of thousands of men and women who work for California’s oil-and-gas industry are absorbing?

Barring a dramatic cultural and policy turnaround, hydrocarbon production in the Golden State will soon die. The fatality’s been a long time coming, and fresh actions by local governments and pols in Sacramento will provide a coup de grâce.

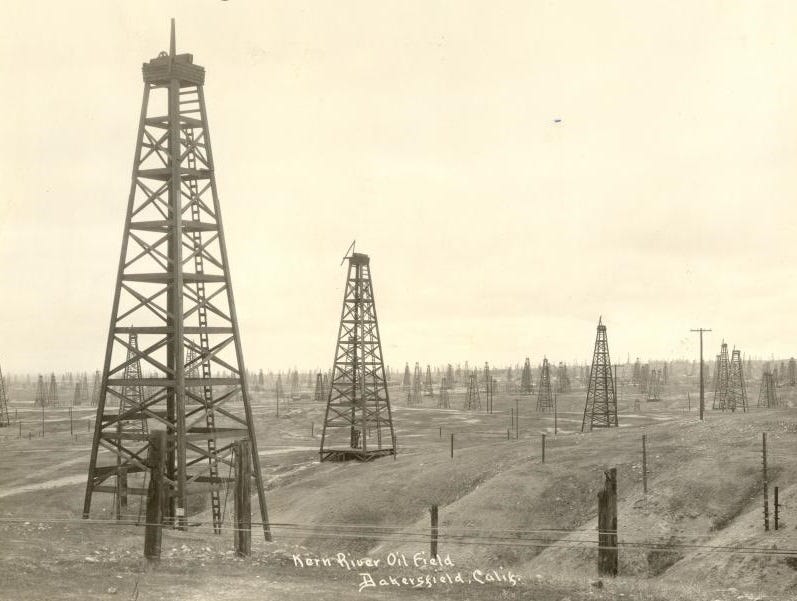

First, a look at history. California was already a petroleum powerhouse when Spindletop made Texas a legitimate competitor. In the 1870s, the Pico Canyon Oilfield, which produced black gold until 1990, set off the boom. The Kern River Oil Field was tapped in 1899, and it remains active. (The Ellwood Oil Field was shelled by a Japanese submarine in 1942. Seriously!)

Among the states, in 1981, California ranked third for onshore petroleum production. (Texas and Alaska were first and second.) But the peak arrived in 1985. By 2021, the Golden State stood at No. 7 nationally, bumped downward by New Mexico, North Dakota, Colorado, and Oklahoma. California was once impressive, though not dominant, in natural-gas production. Unsurprisingly, by 2021, it had tumbled out of the top ten list.

California’s multi-decade lurch to the left — high taxes, runaway regulation — played a role in its hydrocarbon industry’s woes. But what’s happened more recently is different. Bigtime. Climate warriors in elective office aren’t trying to make production difficult. They want to kill it.

In mid-2019, “Gov. Gavin Newsom … imposed a de-facto moratorium on hydraulic fracturing,” and two years later, when legislators failed to prohibit the practice in statute, he “directed the Department of Conservation’s Geologic Energy Management … Division to initiate regulatory action to end the issuance of new permits for hydraulic fracturing … by January 2024.” (Kern County’s commissioners were, understandably, livid.)

In September 2021, “the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to ban new drilling and phase out existing wells in the unincorporated” portion of its jurisdiction, and in January, the Los Angeles City Council followed suit.

Four months ago, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) adopted a “roadmap so that by 2035 100% of new cars and light trucks sold … will be zero-emission vehicles.” The very next month, Newsom signed a bill forbidding “new oil and gas wells, or major retrofitting of existing wells, within … 3,200 feet between the wells and homes, schools, nursing homes and hospitals.” The California Independent Petroleum Association, charging that the law “threatens to further increase California’s already high gas prices by decreasing in-state energy supplies and replacing those barrels with expensive imported foreign oil that contributes greater Greenhouse Gas emissions,” has launched a repeal effort. Best of luck, but in the state that leads the country in eco-lunacy, the smart money’s on the forces of Ed Begley Jr.

Last week, the CARB “unanimously approved a sweeping state plan” — 297 pages — “to battle climate change, creating a new blueprint for the next five years to cut carbon emissions, reduce reliance on fossil fuels and speed up the transition to renewable energy.” The goal is “to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045 or earlier,” in part by reducing “demand for liquid petroleum by 94 percent and total fossil fuel by 86 percent.” While “some California demand for finished fossil fuels (gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel) in 2045” will be tolerated, heat pumps, induction stoves, “carbon capture and sequestration,” wind, solar, energy storage, geothermal, biomass, “sustainable options for walking, biking, and public transit,” etc. will more than compensate.

At about 0.4 percent of the planet’s population, it’s not at all clear that Californians’ enviro-piety can reverse the impending weather apocalypse. But give the state credit for its ambition.

The residents of Loyola, Brentwood, Los Altos, Montecito, and Cupertino will sleep well tonight, knowing that their state is forging ahead to a glorious “green” future. And if tens of thousands of workers in places like Bakersfield (ugh) need to find other livelihoods, well, that’s all part of the “energy transition.” It’s World War Carbon, and collateral damage is inevitable.

Excellent article. For those with short memories, two years ago a bill was drafted by two of our more radical Dem legislators proposing the end to fracking on state lands. Fortunately, it never reported out of committee. NM gets 40 percent of it's revenue from oil&gas. Can you imagine what such a ban would do to state revenues? Don't underestimate the insanity of the left in NM or elsewhere.